“…the romance of the past and the promise of the future.” – Architect, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue

Over the years in California ceramic tiles have integrated themselves into the cultural fabric, beginning with the chain of missions commencing in San Diego in 1769 and stretching as far north as Sonoma, north of San Francisco. Mission San Antonio de Padua in Jolon, Calif., in the hills west of King City, displays floor tiles inscribed with decorative motifs produced by Native Americans under the supervision of Spanish padres in the late 18th century (Fig. 1).

Today in California decorative tiles are everywhere, and they are the centerpiece of the architectural spaces they adorn. A perfect example is the original City Hall in the town of Santa Maria in the central part of the state (Fig. 2). The brightly colored tiles along with the rich earthen roof tiles and pavers – most often found in stark contrast to white stucco facades – have woven their way into the community consciousness. The appeal involves more than simple decoration; Californians have a tendency to “own” their tiles, those in and around their homes as well as those tiles installed in public buildings.

Beginning in 1910 California decorative tiles evolved into two distinct styles, each a synthesis of many elements but both designed to harmonize with the different architectural styles of the period and both clearly recognizable today as unique to the region.

Batchelder Tiles

Nowhere else in the country were tiles made with an earthy appearance akin to the tiles of Ernest Batchelder. In 1910, having left a prestigious job teaching design at Throop Polytechnic Institute in Pasadena, Batchelder opened a school of Arts and Crafts in his backyard garden (Fig. 3) overlooking the Arroyo Seco. Designed to blend into the dark, muted interiors of the bungalow, these handcrafted tiles were most frequently used on fireplace facades and hearths (Fig. 4).

The aesthetic roots of this type of tile can be traced to the Arts and Crafts movement in the eastern United States, specifically to Henry Chapman Mercer and his Moravian tiles from Doylestown, Pa., and from there back to England, northern Europe, and the tiles of the medieval period (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Batchelder’s own fireplace, thought to be created by him for his wife as a wedding gift in 1912.

Fig. 5. Batchelder’s front door with one of Mercer’s tiles embedded above the handle.

The tiles themselves, accented by a distinctive assortment of decorative, struck a chord with the public. By 1912, Batchelder had taken on a partner, Frederick Brown. They established a small factory on South Broadway in Pasadena, as Batchelder himself described, “Down among the gas tanks in a galvanized shed in regions remote from neighborly solitude.”

California China Products Co.

In sharp contrast to Batchelder tiles’ earthy, handcrafted appearance, those with bright colors and geometric designs characterized an entirely different aesthetic. The origins of this aesthetic can be traced to Mexico, Moorish Spain, North Africa and the Middle East: a synthesis of color and design ideally suited to the soon-to-be-popular architectural style that drew inspiration from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego. Initiated for the exposition by architect Bertram Goodhue from his office in New York, these tiles were designed to complement the Spanish Colonial Revival architecture also introduced at the expo.

The contract to produce Goodhue’s tiles for the California Building at Balboa Park was awarded to a recently-formed company in the area, California China Products Co., founded by Walter Nordhoff and his son Charles in 1911 (Fig. 6). Nordhoff, a former journalist with the New York Herald, had recently made a well-advised move out of Mexico just prior to the Revolution where he had been managing his family’s 50,000-acre ranch south of Ensenada.

Having no personal experience with ceramics, Nordhoff hired an impressive team to produce the tiles. The artwork was handled by Wesley Trippett of Redlands Pottery, the earliest known art pottery in Southern California; the glaze man was Walter de Steiguer, a young mining engineer from Missouri; and the master tilewright was an Englishman, Fred Wilde, a 55-year-old, one of the most experienced and respected tile men in the state.

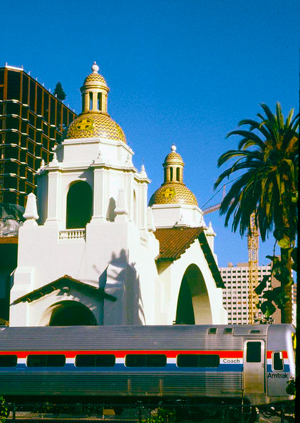

When entering the California Building at Balboa Park, one was immediately struck by the stunning tilework on the wainscot. There was no historic precedent for this bombardment of bright color (Fig. 7). Among those duly impressed by the tilework were the architects John Bakewell, Jr. and his partner Arthur Brown, Jr. of San Francisco, who were in San Diego reviewing their own project, the Santa Fe Railway Depot not far from the park, which was scheduled to be open in time for the exposition (Fig. 8). The architects subsequently chose California China Products to produce the floor and wall tiles accentuated by the striking Santa Fe emblem (Fig. 9). Designs and colors even similar to these had rarely if ever been seen before in the U.S., much less on the West Coast. Even today they are imbued with a quality that tends to inspire.

Fig. 8. The Santa Fe Railway Depot with its twin tiled domes by California China Products.

Fig. 9. The Santa Fe emblem surrounded by California China Products, designed by architects Bakewell & Brown, c. 1914.

Photography by Joseph A. Taylor, Tile Heritage Digital Library.

Sheila A. Menzies and Joseph A. Taylor

Joseph Taylor and Sheila Menzies founded the Tile Heritage Foundation in 1987 in Healdsburg, Ca. This archival library and resource center is dedicated to the preservation of ceramic surfacing materials in the United States. The archives catalog information about historic and contemporary tile companies in the United States, and maintains a collection of over 4,000 historic and contemporary tiles, all of them donated. The non-profit Foundation is maintained by sponsorship, grants, gifts and membership, as well as contemporary tile sales. Visit http://www.tileheritage.org for more information.